Supporting Urdu as an LCTL in the U.S.

Bilingual Performance in Non-Roman LCTL Dual Language Programs

The Initiative for Multilingual Studies is conducting a three-year research study to investigate the relationship between written and oral proficiency in Urdu and English, on the one hand, and students’ academic achievement in a dual language immersion (DLI) program, on the other. The question is important because little is known about DLI outcomes when the partner language is a less commonly taught language (LCTL) that greatly differs from the other partner language, English, in the non-roman script, the right-to-left- text directionality, phonology, and difficulty. The study is creating new measures for a variety of outcomes in both the LCTL and English and for kindergarten through Grade 5. The study is funded by the International Research and Studies, Department of Education.

The findings will contribute to both the teachers and the teaching of Urdu, and LCTL languages in the United States (e.g. South Asian languages). They will serve as a blueprint for others wanting to create successful and accountable DLI programs in LCTLs partner languages in the United States.

The research team is led by Dr. Hina Ashraf, Associate Research Professor, and Co-PI, Prof Lourdes Ortega. They will be assisted by Nishita Grace Isaac, doctoral student, and supported Dr Jamie Schissel, the project evaluator. The findings will contribute to both the teachers and the teaching of Urdu, and LCTL languages in the United States (e.g. South Asian languages).

IMS provided technical assistance to the Urdu-English dual immersion instruction program of Allen Jay Elementary School in North Carolina. The research team visited the school, met the school community and parents, and visited classrooms. The researchers collected data from teachers through interviews, focus groups, and questionnaires for a needs assessment, and provided tailored professional development for the school based on the needs analysis.

Project Evaluation

Dr Jamie Schissel is a researcher and teacher focusing on educational equity in assessment, policy, and teacher education with linguistically diverse communities.

Urdu as a critical language in the U.S.

Urdu is considered a critical language in the United States along with other languages such as Arabic, Hausa, Mandarin, or Turkish, according to a recent report of the Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA, US State Department of Education, 2019). Only about 0.21% Urdu speakers attend schools as English Learners across the United States (OELA, 2017). Under these circumstances, finding Urdu dual language schools in the United States seems like a rare possibility. Yet in North Carolina’s Guilford County, Urdu is ranked fifth out of the hundred and twenty-one languages, and at Allen Jay Elementary, a Guilford County School, the Urdu population is being served!

Allen Jay Elementary School’s Urdu Dual Immersion Program

The Allen Jay Elementary represents a noticeable language demography with a student population that can be roughly divided into three groups: Spanish, English and Urdu. The latter group reflects the vast Urdu-speaking population of High Point and Greensboro counties. Allen Jay is the only public school system that caters to an Urdu language population in the whole of the United States. This is their fifth year of running this program. Currently, the program starts in kindergarten and goes all the way up to Grade 4. The 4th grade is their newest addition.

Dr. Whitney Oakley, Guilford County School Superintendent, explained how passionate she was about building a sustainable Urdu dual immersion program that continues the teaching of Urdu at middle and high school levels.

Outside the school, having an Urdu DLI has increased parents’ engagement with the school, and has opened pathways for positive intercultural understanding and appreciation. Aiming to promote academic achievement through enrichment instead of remediation has also invited students to gain proficiency in both languages, and it has increased their self-esteem, empathy, and global awareness.

Inside the Urdu-English DLI classroom

Observing a DLI program in real-time sheds light on the implementation of the textbook models of dual language programs in the United States. What practices actually occur in the classroom? How do teachers manage Urdu and English in their pedagogy in ways that allow students to develop sustained proficiencies in both languages? How does the school benchmark its curricular and assessment standards in both languages? How are gaps, if any, in the proficiency and literacy practices of both Urdu and English bridged?

Taking the initiative to support and sustain Urdu

The school leadership

Ms. Carla Flores-Ballesteros, initiated the DLI program during her tenure. She herself comes from Mexico and is a native speaker of Spanish. Although Urdu is a foreign language for her, language maintenance has been a professional goal and personal passion. Currently, the program is being led by Principal Elizabeth Callicutt. She and her Dual Language Immersion (DLI) Curriculum Facilitator, Ms. Milay Alvarez, work with native speakers from both the United States and Pakistan who can teach in Urdu, develop materials for teachers and students, and cater to the new and thriving Urdu DLI.

The researchers

Coming from Pakistan, Urdu is one of Ashraf’s family languages. Ashraf is an Urdu and English language-in-education policy researcher, curriculum developer and advisor for secondary and tertiary, teacher education and language proficiency assessment. As such, her interest in supporting Allen Jay ES is organic.

The teachers

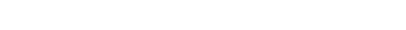

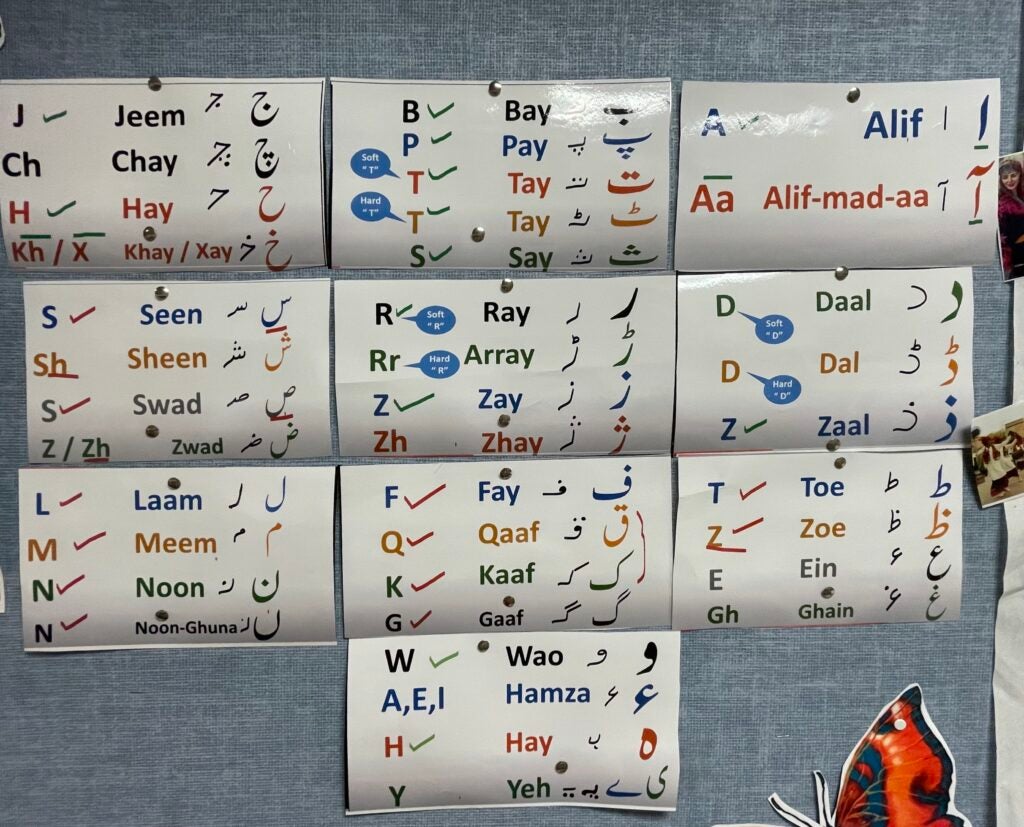

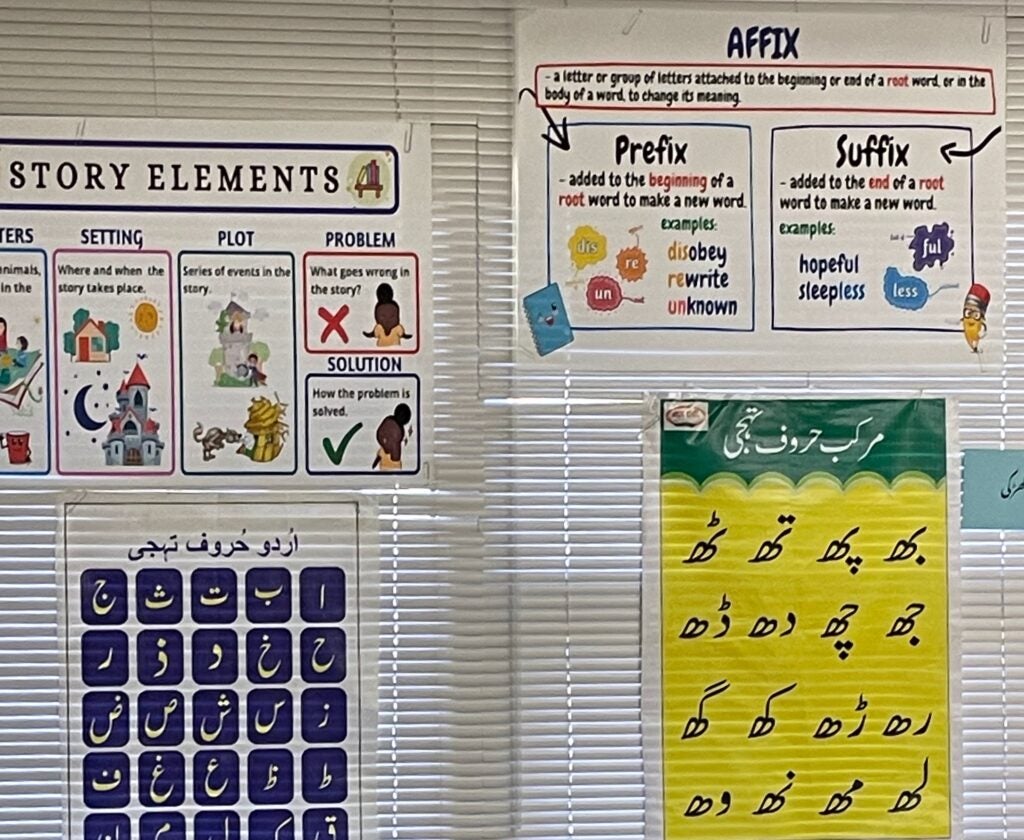

Urdu is a low-resourced language when it comes to digital purposes, and Allen Jay, like many other schools in the U.S., has a strong keyboard orientation. Moreover, the Urdu keyboard is quite different from the English one. These differences place additional demands on the creation of Urdu materials. Yet Allen Jay’s Urdu curriculum staff have put endless hours into creating these teaching materials, both in print and digital format, and then deploying them in the classrooms.

The learners

With clear differences in reading accuracy and reading speed across both languages, Urdu’s right to left orthographic orientation adds to the cognitive competence of heritage students who are learning Urdu after English. In Pakistan, most children either learn Urdu before English or both languages at the same time. Though the phoneme and grapheme relationship in Urdu is pretty straightforward, learning the sound and symbol correspondence across languages, textual granularity, and curriculum mapping at both basic and advanced levels of cognition is complex.

*IMS remains committed to explore avenues that could facilitate and sponsor professional development for teachers of LCTLs in the United States, and especially Allen Jay ES.

With clear differences in reading accuracy and reading speed across both languages, Urdu’s right to left orthographic orientation adds to the cognitive competence of students who are learning Urdu after English. In Pakistan, it is the other way round as most children either learn Urdu before English or both languages at the same time. Though the phoneme and grapheme relationship in Urdu is pretty straightforward, learning the sound and symbol correspondence across languages, textual granularity, and curriculum mapping at both basic and advanced levels of cognition is complex. Urdu is a low-resourced language when it comes to digital purposes, and Allen Jay, like many other schools in the U.S., has a strong keyboard orientation. Moreover, the Urdu keyboard is quite different from the English one. These differences place additional demands on the creation of Urdu materials. Yet Allen Jay’s Urdu curriculum staff have put endless hours into creating these teaching materials, both in print and digital format, and then deploying them in the classrooms.

Outside the school, having an Urdu DLI has increased parents’ engagement with the school, and it has opened pathways for positive intercultural understanding and appreciation. Aiming to promote academic achievement through enrichment instead of remediation has also invited students to gain proficiency in both languages, and it has increased their self-esteem, empathy, and global awareness.